CASE REPORT | https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10001-1349 |

Arteriovenous Malformation of the Prevertebral Region: A Case Report

1Department of General Surgery, Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Sciences, Bellary, Karnataka, India

2Department of Neurosurgery, Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Sciences, Bellary, Karnataka, India

Corresponding Author: Rohith Muddasetty, Department of General Surgery, Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Sciences, Bellary, Karnataka, India, Phone: +91 7760901012, e-mail: rohith.m.setty@gmail.com

How to cite this article Muddasetty R, Sidram V. Arteriovenous Malformation of the Prevertebral Region: A Case Report. Int J Head Neck Surg 2018;9(3):113–115.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

ABSTRACT

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are a congenital lesion which can present in any period of life. They are slow-growing lesions. The most common site is the brain. Extracranial lesions are quite rare. They can be treated by surgical excision or by endovascular therapy. Here, we report a case of AVMs of the prevertebral space.

Keywords: Arteriovenous malformation, Prevertebral space, Vascular anomalies.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular anomalies, by Mulliken and Young, were classified as hemangiomas and vascular malformations. Hemangiomas consist of endothelial hyperplasia and enlargement, while vascular malformations consist of progressive ectasia of the vessels lined by thin endothelium.1–3

Vascular or AVMs are a result of an error in embryogenesis, always present at birth, can manifest at any age, and can grow with growth of the child. They can be further divided into slow flow lesions (veins, capillary, and lymphatic) and fast flow lesions (arterial, arteriovenous fistulas, or shunts). Around 51% of the lesions are present in the head and neck regions with a majority of them occurring within the cranium. Treatment options include surgical excision or endovascular techniques. The endovascular approach includes embolization, coiling, and injecting sclerosants.4

AVMs of the prevertebral region are a rare presentation. It is a slow-growing lesion but a risk of involvement of the brachial plexus, nerve roots, and vertebral arteries is present. The accessory nerve lies superficial to prevertebral fascia.

CASE DESCRIPTION

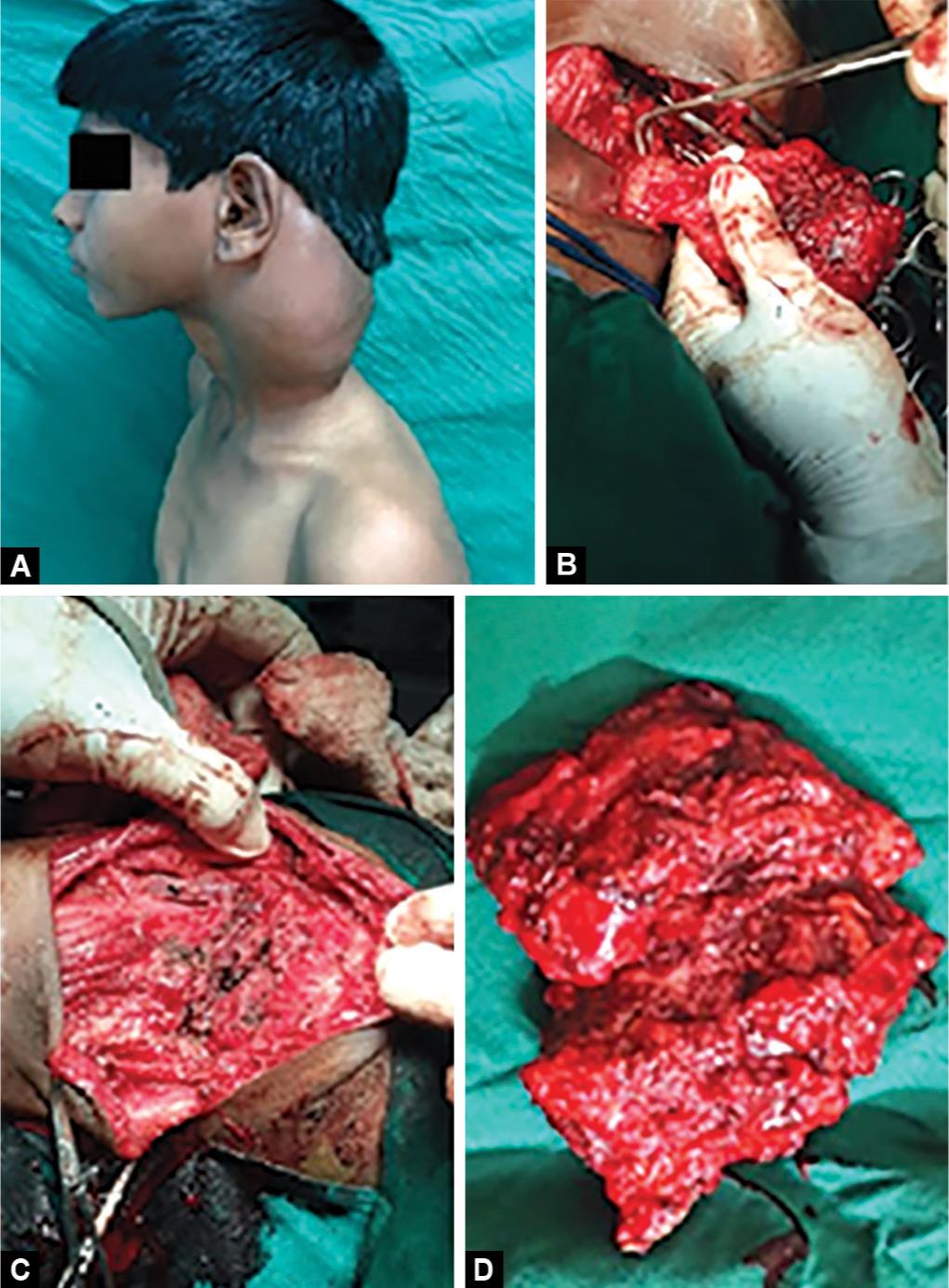

A male child, 12-year-old, presented with a huge swelling in the left side of the neck (Fig. 1). Parents had noticed the swelling around 7 years back, it gradually increased in size. There is no history of pain, restriction of neck movements, paresthesia, or weakness of the left upper limb. Swelling was of variable consistency, posterior extending up to cervical vertebra. Transilluminance was absent, and it was not compressible. No bruits over the swelling. The skin over the swelling was normal with no rise in the temperature. Ultrasonography of the neck showed a cystic lesion with multiple septations. On needle aspiration, bloody aspirate was noted. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck was suggestive of a vascular malformation (Fig. 2).

Surgical excision was planned. During surgery, a left transverse neck incision was taken and flaps were raised both superiorly and inferiorly (Fig. 1). The sternocleidomastoid muscle was retracted anteriorly. The lesion was separated from carotid and internal jugular vessels anteriorly; brachial plexus, subclavian vessels, omohyoid, and scalene muscles inferiorly; and base of the skull superiorly. Posteriorly, the lesion was found to extend up to prevertebral space of the cervical vertebra, which was released. During the dissection, the above-mentioned structures along with the left phrenic nerve and the left vagus nerve were identified. Adequate hemostasis was achieved and neck incision was closed after keeping a drain.

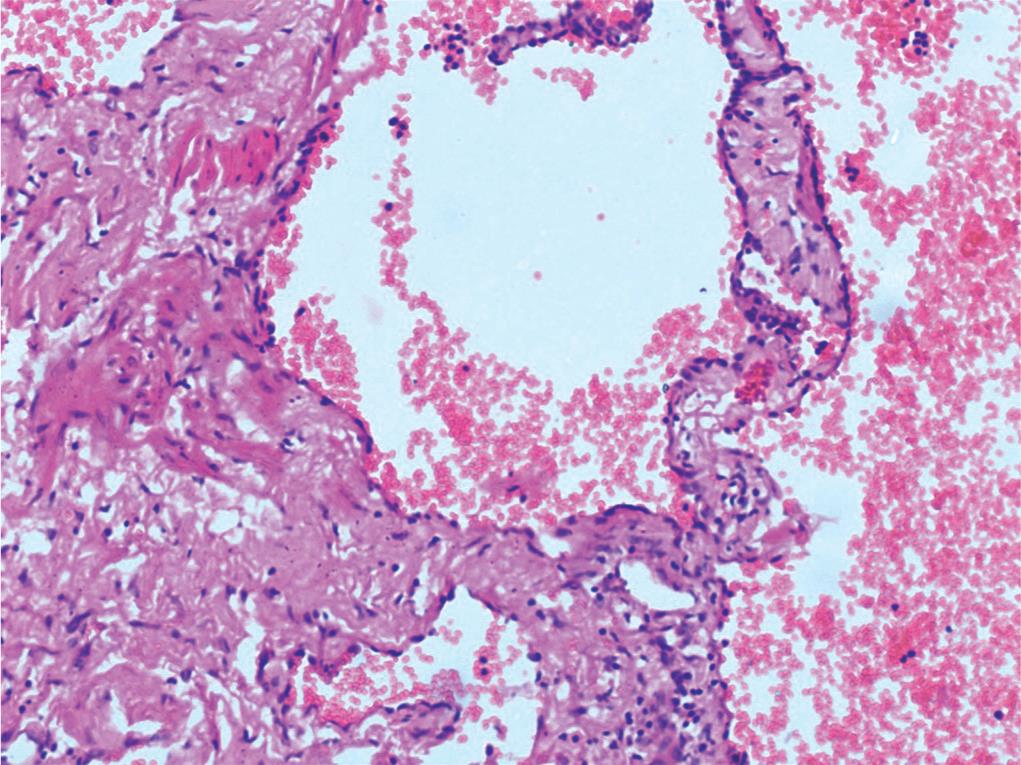

The postoperative period in the hospital was uneventful. Follow up during the period of 2 months is also uneventful. Histopathological examination of the specimen showed it to be an AVM (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

AVMs occur due to failure of complete involution of the fetal capillary bed in the primitive retiform plexus resulting in the development of the abnormal connection between arteries and veins. This leads to progressive engorgement and destruction of the tissue and may lead to venous hypertension and cardiac failure due to the high output state.5,6 They can be present in any part of the body; however, intracranial is the most common site. Extracranial AVMs are quite rare.7 It is proposed that a defect in ephrins or its receptors is involved in the formation of the AVMs.8,9 The cause of expansion of the AVM is thought to be dilatation due to increased pressure and flow and ischemia due to trauma. AVM progresses through four stages classified by the Schobinger clinical staging.10,11 Stage I lesions are in the quiescent phase, asymptomatic, usually from birth to adolescence. Stage II lesions are in the progressive phase, usually occur in adults. The expansion at the lesion occurs at puberty, pregnancy, and trauma. In addition, some forms of treatment like incomplete arterial ligation and partial excision can also stimulate a quiescent lesion to progress. Stage III lesions mimic stage II lesions, but associated with tissue destruction. They present with ulceration, hemorrhage, and pain. Lytic bone lesions may also be present. Stage IV lesions present with cardiac decompensation.

Figs 1A to D: Clinical picture. (A) Swelling in the left side of neck; (B) Intraoperative picture showing lesion of the lesion; (C) After the removal of the lesion; (D) The lesion after excision

Fig. 2: MRI picture

Fig. 3: Histopathological picture

AVMs are diagnosed clinically and radiologically. Color Doppler examination can show the flow characteristics. Magnetic resonance angiography is a noninvasive method of analyzing the flow and extent of the lesion. Angiography can be done to know the feeding vessel when embolization is planned.

Many treatment options are available for AVM. Observation may be used as a temporary measure for asymptomatic lesions or in specific conditions like pregnancy and extreme age. Arterial ligation was used in the past purely as a symptomatic measure or before surgery.12–14

At present, selective angiographic embolization is the first line of management. Occlusion can be done by coils, balloon, or liquid glue.12,15 Radical surgical resection as in cancer is also proposed. Improper surgical resection may lead to recurrence of the lesion. In the above-described case, surgical excision was a feasible option.

CONCLUSION

AVMs are rare lesions of the prevertebral region. They can lead to chronic pain, ulceration, hemorrhage, and tissue destruction. They may progress to venous hypertension and cardiac decompensation. Some kind of intervention is, thus, required.

REFERENCES

1. Mulliken JB, Young AE. Vascular birthmarks: hemangioma and malformations. WB Saunders; 1988.

2. Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982;69:412–422. DOI: 10.1097/00006534-198203000-00002.

3. Waner M, Suen JY. Management of congenital vascular lesions of the head and neck. Oncology 1995;9:989–994.

4. Hurwitz DJ, Kerber CW. Hemodinamic considerations in the treatment of arteriovenous malformations of the face and scalp. Plast Reconstr Surg 1981;67:421–432. DOI: 10.1097/00006534-198104000-00001.

5. Sunagawa T, Ikuta Y, et al. Atreriovenous Malformation of the ring finger. J Comput Assit Tomogr 2003;27:820–823. DOI: 10.1097/00004728-200309000-00023.

6. Burrows PE, Mulliken JB, et al. Pharmacological treatment of a diffuse Arteriovenous Malformation of upper extremity in a child. J Craniofacial Surg 2009;20 (Suppl 2):1–5. DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181927fle.

7. Wu JK, Bisdorff A, et al. Auricular Arteriovenous Malformation. Plast Reconst Surg 2005;115:985–995. DOI: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000154207.87313.DE.

8. Wang HU, Chen ZF, et al. Mollecular Distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins. Cell 1998;93:741–753. DOI: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1.

9. Gault J, Sarin H, et al. Pathobiology of brain cerebrovascular malformation. Neurosurgery 2004;55:1–17.

10. Enjolres O, Logeart I, et al. Arteriovenous malformation. Ann Dermatol Venercol 1999;127:17–22.

11. Lawson ND, Scheer N, et al. Notch signaling required for arteriovenous differentiation during embryonic life. Development 2001;128:3675–3683.

12. Giauoi L, Princ G, et al. Treatment of vascular malformations of the mandible: a description of 12 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;32:132–136. DOI: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0268.

13. Sakkas N, Schramm A, et al. Arteriovenous malformation of the mandible: a life-threatening situation. Ann Hematol 2007;86:409–413. DOI: 10.1007/s00277-007-0261-2.

14. Persky MS, Yoo HJ, et al. Management of vascular malformations of the mandible and maxilla. Laryngoscope 2003;113:1885–1892. DOI: 10.1097/00005537-200311000-00005.

15. Yoshiga K, Tanimoto K, et al. High-flow arteriovenous malformation of the mandible: treatment and 7-year follow-up. Brit J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;41:348–350. DOI: 10.1016/S0266-4356(03)00132-3.

________________________

© The Author(s). 2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.