INVITED REVIEW ARTICLES |

https://doi.org/10.5005/jp-journals-10001-1517 |

Type I Thyroplasty and Arytenoid Adduction: Review of the Literature and Current Clinical Practice

1,2Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, Division of Laryngology, Mount Sinai Health System, New York, USA

Corresponding Author: Sarah K Rapoport, Mount Sinai Health System, 1 Gustave L. Levy Place, Annenberg 10-40 Box 1189, New York, NY 10029, USA, Phone: +1 (212) 241-1377, e-mail: sarah.k.rapoport@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Aim: Dysphonia resulting from glottic insufficiency or vocal fold immobility can be a distressing and debilitating condition. The ability to medialize a vocal fold and reposition an immobile arytenoid to allow patients to regain quality, stamina, and reliability of their voice can be achieved through type I medialization thyroplasty with concurrent arytenoid adduction when indicated.

Background: Medialization thyroplasty and arytenoid adduction techniques have been honed and reliably performed for decades. The durability of these procedures has been well demonstrated. Additionally, they are routinely performed under local anesthesia with moderate anesthetic sedation enabling frail patients, suffering from glottic insufficiency who are otherwise poor surgical candidates, the opportunity to pursue laryngeal framework surgery and regain vocal strength while risking low overall morbidity.

Review results: Understanding how to apply the nuances of these surgeries can yield reliable and successful outcomes. Appreciating these subtle details in the context of the historical development of these procedures is beneficial for any otolaryngologist performing these procedures.

Conclusion: Type I thyroplasty and arytenoid adduction procedures have been meticulously refined over time. As a result they are technically elegant and simple procedures that rely on intraoperative precision to optimize postoperative voice outcomes.

Disclosures: Please note, this manuscript has not been submitted or presented elsewhere prior to submission here. All authors have no conflicts of interest, sources of external funding related to this publication, or financial disclosures related to this publication to declare.

How to cite this article: Rapoport SK, Courey MS. Type I Thyroplasty and Arytenoid Adduction: Review of the Literature and Current Clinical Practice. Int J Head Neck Surg 2021;12(4):166-171.

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of interest: None

Keywords: Arytenoid adduction, Dysphonia, Implant carving, Isshiki type I, Medialization laryngoplasty, Medialization thyroplasty, Vocal fold atrophy, Vocal fold paralysis

BACKGROUND

Fifty years after the central tenets of laryngeal framework surgery were systematically published by Nobuhiko Isshiki,1 laryngologists are routinely incorporating the medialization laryngoplasty and arytenoid adduction in their clinical practice. As many laryngologists strive to perfect the nuances of these procedures that can result in restoring vocal strength and quality, it behooves laryngologists to keep in mind the historical context of how these surgeries were devised through the creativity and persistence of our predecessors.

Although Isshiki honed and popularized the medialization thyroplasty procedure in the mid-1970s, the concept of applying lateral compression to medialize a vocal fold precedes his work. Wilhelm Brunings first experimented with restoring glottic insufficiency by injecting paraffin into the vocal fold in 1911 in a patient with presumed recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis. Erwin Payr then conceptualized applying medial compression to the vocal fold in 1915 by making a U-shaped incision along the thyroid ala to create a pedicled cartilage flap that could be depressed inward to compress the vocal fold. Though novel in theory, the actual medialization gained from Payr's pedicled flap was limited, restricting the technique's utility. Decades later, in the 1950s, Yrgo Meurman and Odd Opheim both revived the idea of medializing the vocal fold by using various cartilage grafts inserted between the thyroid cartilage and inner perichondrium to establish vocal fold medialization. Both Meurman and Opheim faced severe post-procedural edema and hematoma formation requiring tracheostomy.1,2 Despite the acute complications from their surgeries, Meurman and Opheim also demonstrated improved voice quality with their surgical procedures which spurred their contemporaries to continue exploring and revising these techniques.

Shortly thereafter, Isshiki published his paper describing his famed and eponymous four types of laryngoplasty. In the discussion he predicted that the functional utility of his type I thyroplasty to improve both tension and position of an immobile or atrophic vocal fold would it make it the most useful of the four thyroplasty techniques he described.3 Given the high incidence of dysphonia due to glottic insufficiency, as well as the elegance and ease of performing Isshiki's type I thyroplasty under moderate sedation, his prediction has held true.

Yet performing the type I medialization thyroplasty alone often seemed insufficient as it failed to resolve large posterior glottic gaps or restore the height mismatch of a paralyzed vocal fold. Similar to the medialization thyroplasty procedure, manipulation of the arytenoid cartilage faced decades of variations before becoming the arytenoid adduction procedure familiar to us today.

In 1948, Lewis F Morrison developed a technique for transposition and rotation of the arytenoid cartilage with his Reverse King Operation for cases of bilateral abductor paralysis. But this technique was technically challenging which discouraged many from incorporating it into practice.1 K Mundnich then published a procedure in 1970 where the arytenoid was pulled and fixed to the thyroid cartilage which resulted in tensing the vocal fold while shifting it medially. Isshiki later revised this procedure in 1978, describing the now-familiar arytenoid adduction procedure where pulling the lateral, muscular process of the arytenoid restored vocal fold height while also effectively adducting the vocal fold.4

Rationale and Tips for Optimal Technique for Type I Medialization Thyroplasty

The goal of the medialization thyroplasty procedure is to modify both the position and tension of the vocal fold to restore glottic closure. Standard clinical indications for surgery are glottic insufficiency due to organic or traumatic atrophy of one or both vocal folds such as vocal fold scarring, bowing, and paresis, or immobility of the vocal fold as seen in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. In practice, anyone presenting with glottic incompetence that results in poor phonation and/or weak cough can be considered a candidate for medialization laryngoplasty.5 The application of early medialization laryngoplasty has been demonstrated to improve rehabilitation in patients with high vagal nerve injuries by restoring glottal competence, thereby potentially reducing gross aspiration and improving voice quality in the setting of high vagal nerve paralysis.6

Jamie Koufman, who popularized Isshiki's medialization thyroplasty technique in the United States in the late 1980s, standardized her procedural method using a mathematical calculation to determine optimal thyroplasty window height and size, depending on a patient's biologic gender. James Netterville, together with his surgical team at Vanderbilt University, later refined Koufman's surgical technique and devised surgical instruments to improve the operative procedure. Here we review critical parts of the medialization thyroplasty with a focus on fundamental components of the procedure as described by Netterville, since his variations are currently more commonly practiced among laryngologists. It is paramount to remain vigilant while performing this procedure as we believe achieving precision in these key steps can make a difference in yielding successful outcomes in medialization laryngoplasty.

Operative room and anesthesia considerations are well-documented in the literature, so in an effort to focus on this article's goals of rationale and surgical technique we will not directly address these concepts here. When we perform the procedure our patients are placed under moderate sedation. Once the patient is positioned properly, prior to prepping and sterilely draping the patient, we inject a 1:1 local subcutaneous anesthetic block of 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine and 0.5% marcaine extending from the hyoid bone to the cricoid cartilage. Some surgeons also inject down through the strap muscles to the thyroid cartilage. Due to the longer half-life of Marcaine compared with lidocaine with epinephrine, this combination of local anesthesia provides short and intermediate term local anesthesia during the procedure.

To perform a successful medialization thyroplasty it is not required to use transnasal indirect flexible videolaryngoscopy during surgery, however it can provide beneficial intraoperative feedback and, therefore, we recommend it. While the degree of adduction and size of the implant vary based on voice quality determined by intraoperative acoustic feedback from the patient, visual feedback from the transnasal laryngoscope can prevent a surgeon from medializing the false vocal fold or ventricle with placement of an implant. As we discuss later, this direct visualization afforded by the transnasal laryngoscope can also help prevent over-adduction of the vocal process during an arytenoid adduction procedure.4,7

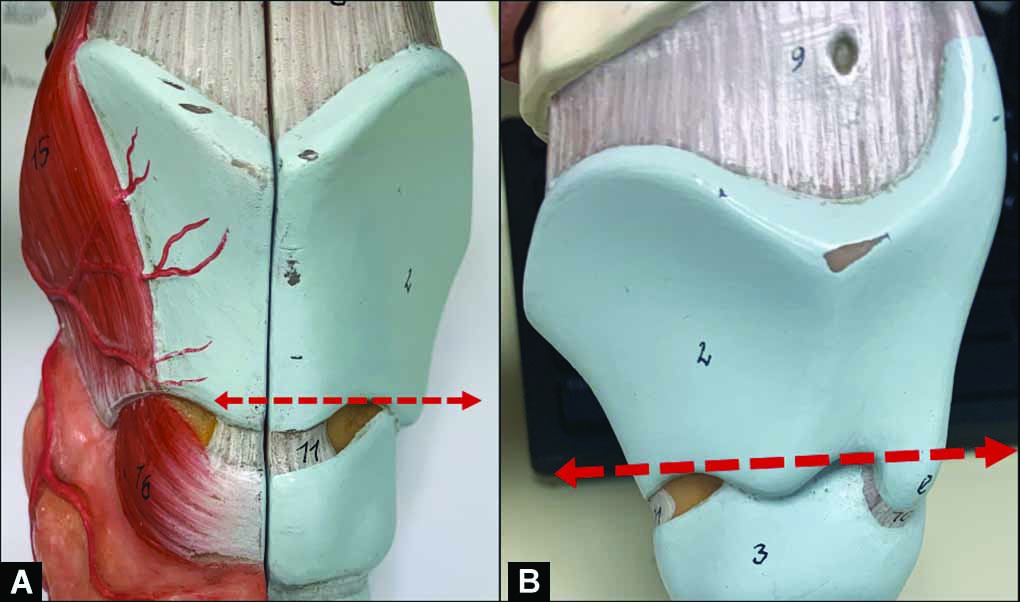

To begin the procedure, expose the larynx through an approximately 5 cm incision overlying the inferior, mid-thyroid cartilage extending along the side to be implanted. Elevate subplatysmal flaps to the hyoid bone and over the cricoid ring. Wide exposure facilitates adequate medialization and allows arytenoid adduction if needed. Exposure is also facilitated by separating the sternohyoid from the underlying strap muscles that attach directly to the thyroid cartilage. Then elevate the perichondrium along with the sternothyroid, thyrohyoid and constrictors that attach to the larynx from the cartilage and retract it to help preserve it. Use the thyroplasty window template measuring 5 x 12 mm to mark out the size of the window. Proper positioning of the thyroplasty window is critical to successful placement of the thyroplasty implant. The window must be positioned parallel to the lower border of the thyroid cartilage. To ensure the plane of the thyroplasty window is parallel to the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage, one must conceptualize how the lower border of the thyroid cartilage is formed between the anterior inferior thyroid cartilage and the portion of the cartilage that extends behind the muscular process7(Fig. 1). While these landmarks may seem simple to locate in theory, surgeons must take caution during this step because if the inferior extension of the muscular process is used to approximate the inferior border of the thyroid cartilage then the direction of the thyroplasty window will be malpositioned.

Figs 1A and B: The thyroplasty window must be positioned parallel to the lower border of the thyroid cartilage, demonstrated by the dashed red lines superimposed on the anterior (left image) (A) and lateral (right image) (B) views of the thyroid cartilage here. Note how the line is parallel to the portion of the inferior thyroid cartilage that extends behind the muscular process.

After establishing the plane of the window, determine its position. By creating a relatively large window and placing the window as low as possible, both the upper and lower mass of the vocal fold can be located within the window. We recommend maintaining a 3-mm inferior strut between the inferior window and inferior thyroid cartilage border to prevent fracturing the thyroid cartilage when placing the implant. If the inferior border fractures, then the anterior-posterior dimension of the larynx on the involved size is compromised as the muscular pull results in shortening of the hemilarynx making alignment difficult if not impossible. Placement of the anterior thyroplasty window differs based on the natural angle of the patient's thyroid cartilage which commonly correlates with biological gender: a distance of 5 mm from the anterior thyroid cartilage is used in women since the angle formed by the prow of their thyroid cartilage is more obtuse, whereas a distance of 7 mm from the anterior thyroid cartilage is used for men since their laryngeal cartilage is more acute.2,3,7 Thyroplasty windows placed too anteriorly risk over medializing the anterior one-third of the vocal fold and windows placed too high risk medializing the upper mass, false fold, and ventricle. Both situations can compromise the quality postoperative voice outcomes.

Once the thyroplasty window is made, some surgeons attempt to separate the inner perichondrium of the thyroid cartilage. These surgeons often cut the window with a saw or drill believing that they can cut cartilage and that the powered instrumentation stops at the perichondrium. They do not account for the attachment of the thyroarytenoid muscle fibers to the cartilage itself nor the variable thickness and completeness of the perichondrium within and between patients. They report that keeping the inner perichondrium intact lessens the likelihood of implant infection due to breach of the laryngeal mucosa. However, we believe that medialization cannot be adequately achieved without either elevating the entire ipsilateral perichondrium or carefully incising this layer of perichondrium while attempting to keep the fascia of the thyroarytenoid muscle intact and freeing the thyroarytenoid muscle fascia from the perichondrium.

At this point in surgery an instrument is used to identify the level of the upper edge and lower edge of the vocal fold within the window and to measure the dimensions of the silastic implant needed to generate appropriate medialization. To prevent medialization of the false vocal fold, ventricle, and upper mass it is often common to maintain the plane of maximal medialization along the inferior edge of the thyroplasty window.7 While manipulating the angle of medialization of the vocal fold with the longer edge of the depth gauge, ask the patient to phonate and measure maximum phonation time. Once you are satisfied that optimal phonation is achieved, record the depth of maximal medialization as well as how far posterior within the window the point of maximal medialization should sit. These measurements can then be marked out on the silastic block that will be used to carve the implant.

Pearls for Implant Carving

It is our practice to precarve our implants on a Firm Consistency Silicone Block for Prosthesis (Bentec Medical, Inc. Ref # PR 88,032-23) to maximize our efficiency intraoperatively. Since the thyroplasty window size remains a standard size for each implant, we use the window size gauge to measure a 5 x 5 mm handle on the silastic block preoperatively (Figs. 2A and B ). We then confirm that the proposed handle, viewed here as the central ridge in the block, is indeed 5 mm wide (Fig. 2C). Once this measure is confirmed, we use a 22-blade knife to cut out two lateral strips of silastic from the block (Figs. 2D and E ) leaving us with a silastic block with a precarved handle (Fig. 2F). These prepared blocks can be sterilized prior to surgery, and made available in the operating room to streamline implant carving.

Figs 2A to F: (A to E) When possible, we precarve the handles of our thyroplasty silastic implant blocks. These prepared blocks can be sterilized prior to surgery, and made available in the operating room to streamline implant carving. F: (F) Carving done

Intraoperatively, once we have measured the point of maximal medialization, we mark our block to reflect the point of maximal medialization along the appropriate length of the window (Fig. 3A). With the point of maximal medialization marked out, we place our implant in the thyroplasty carving handle and use a 22-blade to remove the excess silastic to carve our implant (Fig. 3B). As we remove the excess silastic to form the implant we take care to leave the point of maximal medialization intact. We always double-check that the height of the point of maximal medialization remains intact after carving out the implant (Fig. 3C) before removing the silastic block from the handle and cutting the handle of the implant to fit the thyroplasty window (Fig. 3D).

Figs 3A to D: Intraoperatively, once we have determined the size of the implant, we carve our implants. First, we mark out where the point of maximal medialization should sit along the length of the thyroplasty window (A). Then we use a 22-blade knife to remove the excess silastic from the implant block (B). After carving the block, we re-measure and confirm that the length of the point of maximal medialization has remained intact during our carving process (C). Lastly, we cut the excess silastic from the handle of the block so that the handle will fit in the thyroplasty window (D).

Rationale and Tips for Optimal Technique for Arytenoid Adduction

In Isshiki's original paper examining the outcomes of his type I thyroplasty surgeries, he noted that medialization alone did not resolve the difference in level between the bilateral vocal folds at the level of the vocal process. As others further developed Isshiki's technique for medialization laryngoplasty with a silastic implant, they observed that patients with large posterior glottic gaps who underwent medialization alone were often left with persistent posterior commissure insufficiency.8 Additionally patients with severe paralysis demonstrated prolapsing arytenoid cartilage or an arytenoid that jostled from instability each time it the mobile arytenoid attempted to close against the contralateral cartilage.

These limitations drove Isshiki to develop the arytenoid adduction procedure, which can be performed either alone or as an adjunct to his type I thyroplasty surgery. In combination, the medialization laryngoplasty and arytenoid adduction procedures can provide vocal fold medialization, closure of the posterior commissure, and restoration of symmetric vertical height between both vocal folds to maximize closure of the both the upper and lower masses during vibration.

In cases where an arytenoid adduction is needed in addition to a medialization laryngoplasty, the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage must be exposed. Isshiki described separating the cricothyroid joint. However, this step leads to instability of the thyroid lamina on the cricoid ring and shortening of the ipsilateral hemilarynx. Therefore, we expose the posterior border of the thyroid cartilage by dissecting lateral to the strap muscles and elevating the inferior constrictor muscle off of the thyroid cartilage. We then use a Kerrison Rongeurs to excise thyroid cartilage, while keeping the cricothyroid joint intact, preserving the anteroposterior stability and enabling direct access to the muscular process of the arytenoid. While one surgeon uses a double-prong skin hook to rotate the thyroid cartilage medially, the second surgeon carefully uses two Kittner gauzes to separate the pyriform sinus mucosa from the arytenoid so that access to the muscular process of the arytenoid is unobstructed. As described by Netterville, we then pass a double-armed 4-0 Prolene suture twice through the muscular process of the arytenoid and its immediately adherent soft tissue attachments. The pull of the sutures on the arytenoid recreates the pull of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle on the muscular process of the arytenoid so that the cartilage is rotated into an adducted position.

These two sutures are passed anteriorly through the thyroplasty window. Positioning of these traction sutures determines the degree of arytenoid adduction, so confirming both the degree and angle of tension on the sutures on the transnasal videolaryngoscope intraoperatively is particularly useful. Once the ideal position of the suture is determined, the superior arm of the suture is passed through the anterior thyroid cartilage medial to the thyroplasty window and the inferior arm of the suture is passed just inferior to the midline thyroid cartilage through the cricothyroid membrane. After gentle traction of these sutures confirms appropriate repositioning of the arytenoid, the silastic implant can be placed into the thyroplasty window and the arytenoid adduction sutures can be knotted and secured external to the thyroid cartilage.

Although arytenoid adduction has been shown to result in significant resolution of posterior glottic gap while also affecting vocal fold position and pliability,8 it is not the only option for restoring arytenoid position in cases of vocal fold paralysis. Other authors describe the adduction arytenopexy as an alternative to the arytenoid adduction. These authors suggest that Isshiki's arytenoid adduction risked excessive medial rotation of the vocal process since it did not provide simultaneous simulation of the interarytenoid, lateral thyroarytenoid, and posterior cricoarytenoid muscles to balance the adductive pull of the lateral cricoarytenoid muscle recreated on the arytenoid by the adduction sutures.9,19 These authors propose that the adduction arytenopexy results in a more optimal sound production through improved simulation of the biomechanics of glottal closure.

The adduction arytenopexy is performed by opening the lateral cricoarytenoid joint and using suture to affix the muscular process of the arytenoid to the posterior cricoid cartilage. Unlike Isshiki's adduction procedure, this arytenopexy pulls the arytenoid posteriorly, superiorly and medially. As a result, the arytenoid is repositioned in multiple dimensions resulting in a more organic realignment of the joint in cases of severe posterior glottic insufficiency.10

Risks and Complications of Medialization Thyroplasty and Arytenoid Adduction

Immediate and delayed complications from medialization laryngoplasty, although uncommon, can occur due to several causes. Airway edema, hematoma, and prosthesis extrusion have all been reported in low numbers. In a large-scale national survey of otolaryngologists who perform these procedures, airway complications requiring intervention were noted to occur more in cases where medialization laryngoplasty was performed in conjunction with arytenoid adduction than from medialization alone. Rates of complications from these procedures were noted to be inversely proportional to a surgeon's individual experience with these surgeries.11 Even so, the reported tracheostomy rate for medialization laryngoplasty alone versus medialization with concurrent arytenoid adduction were 0.35 and 1.7%, respectively.12 These findings support the overall safety of medialization thyroplasty and arytenoid adduction, especially when performed by laryngologists whose clinical volume in these specific surgeries are higher than those of other otolaryngologists.

Revision rates in medialization laryngoplasty were also quoted to be quite low, and demonstrated a 90% likelihood to result in improved patient-perceived voice outcome.11 The majority of patients seeking revision thyroplasty complained of persistent dysphonia, while a smaller group of patients presented with dysphagia and dysphonia or dyspnea.13 The most common causes for early failed medialization were arytenoid malrotation resulting in persistent posterior glottic gap, and incorrect implant position and size failing to result in adequate vocal fold medialization. Delayed failures of medialization thyroplasty, although even less common, were due to subsequent vocal fold atrophy and—very rarely—a foreign body reaction to the implant.14 Minor vocal fold hematomas were among the most frequently seen complications from medialization thyroplasty and were not associated with airway compromise.15

Although complications from medialization thyroplasty and arytenoid adduction are uncommon, they can often be addressed and resolved to yield patient satisfaction with their voice. Management of patients with acute complications usually requires airway stabilization. After stabilization of the airway and resolution of any edema or hematoma, the patient can be managed similar to delayed complications: videostroboscopy and CT scan of the larynx can prove helpful in identifying the underlying issue.14 In cases of persistent posterior glottic gaps or arytenoid malrotation, performing an arytenoid adduction can restore the patient's voice quality. Whereas improper size and/or placement of an implant can be resolved through surgical exploration and meticulous surgical technique to correct these errors.

Shift from Silastic Implants to Gore-tex Sheets in Medialization Thyroplasty

The shift to using Gore-tex (expanded polytetrafluoroethylene) sheeting in medialization laryngoplasty surgery as an alternative to individually carved silastic implants was introduced by Henry Hoffman and Timothy McCulloch in 1996.16 Their idea was to further simplify the procedure by eliminating the need to carve a silastic implant for each individual patient. This alternative to carving a distinct silastic block in each surgery provided surgeons a chance to reduce procedural operative time which was considered the biggest risk for the dreaded complication of postoperative airway edema.

In truth, carving silastic implants is an intricate process that many find difficult to reproduce intraoperatively, especially when facing underlying pressure as the principal surgeon to prevent potential patient complications by reducing operative time. Gore-tex sheeting allowed for incremental adjustment of vocal fold position while eliminating the need for special instrumentation trays such as those required for implant carving. The implantable material also had an established safety profile, making it convenient to incorporate into the surgical technique. These features of Gore-tex expanded the feasibility of medialization laryngoplasty while reducing potential risk.17 And, most importantly, use of Gore-tex implants for medialization laryngoplasty demonstrated comparable voice outcomes to patients who had undergone medialization with silastic implants.18

It is important to note that the same complications that exist for medialization thyroplasty with silastic implant—namely, airway edema, implant extrusion, and insufficient medialization—still exist in cases of medialization laryngoplasty with Gore-tex implants. After all, any surgery carries risk. Regardless of which procedural technique is employed for vocal fold medialization, there is no substitute for a surgeon's clinical judgement and attention to operative precision. Still, it is always worthwhile to have multiple successful approaches to solve a surgical problem, and the option to use Gore-tex implants in lieu of silastic blocks provides surgeons with a dependable alternative implant.

CONCLUSION AND CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

The type I medialization thyroplasty and arytenoid adduction procedures have been meticulously refined over time. As a result they are technically elegant and unembellished procedures that rely on intraoperative precision to optimize postoperative voice outcomes. Understanding how to apply the nuances of these surgeries can lead to reliable, successful voice outcomes in patients with glottic insufficiency. Appreciating the subtle details of these procedures in the context of their historical development is beneficial for laryngologists performing these procedures.

REFERENCES

1. Isshiki N, Morita H, Okamura H, et al. Thyroplasty as a new phonosurgical technique. Acta Oto-laryngologica 1974;78(1-6):451-457. DOI: 10.3109/00016487409126379

2. Koufman JA, Isaacson G. Laryngoplastic phonosurgery.Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1991;24(5):1151-1177. DOI: 10.1016/S0030-6665(20)31073-2

3. Isshiki N, Okamura H, Ishikawa T. Thyroplasty type I (lateral compression) for dysphonia due to vocal cord paralysis or atrophy. Acta Otolaryngol 1975;80(1-6):465-473. DOI: 10.3109/00016487509121353

4. Isshiki N, Tanabe M, Sawada M. Arytenoid adduction for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Arch Otolaryngol 1978;104(10):555-558. DOI: 10.1001/archotol.1978.00790100009002

5. Woo P. Arytenoid adduction and medialization laryngoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2000;33(4):817-840. DOI: 10.1016/s0030-6665(05)70246-2

6. Billante CR, Clary J, Sullivan C, et al. Voice outcome following thyroplasty in patients with longstanding vocal fold immobility. Auris Nasus Larynx 2002;29(4):341-345. DOI: 10.1016/s0385-8146(02)00020-2

7. Netterville JL, Stone RE, Civantos FJ, et al. Silastic medialization and arytenoid adduction: The vanderbilt experience. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1993;102(6):413-424. DOI: 10.1177/000348949310200602

8. Chang J, Schneider SL, Curtis J, et al. Outcomes of medialization laryngoplasty with and without arytenoid adduction. Laryngoscope 2017;127(11):2591-2595. DOI: 10.1002/lary.26773

9. Zeitels SM, Hochman I, Hillman RE. Adduction arytenopexy: A new procedure for paralytic dysphonia with implications for implant medialization. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 1998;173:2-24.

10. Zeitels SM, Mauri M, Dailey SH. Adduction arytenopexy for vocal fold paralysis: indications and technique. J Laryngol Otol 2004;118(7):508-516. DOI: 10.1258/0022215041615263

11. Rosen CA. Complications of phonosurgery: Results of a national survey. Laryngoscope 1998;108(11 Pt 1):1697-1703. DOI: 10.1097/00005537-199811000-00020

12. Weinman EC, Maragos NE. Airway compromise in thyroplasty surgery. Laryngoscope 2000;110(7):1082-1085. DOI: 10.1097/00005537-200007000-00003

13. Tucker HM, Wanamaker J, Trott M, et al. Complications of laryngeal framework surgery (phonosurgery). Laryngoscope 1993;103(5):525-528. DOI: 10.1288/00005537-199305000-00008

14. Woo P, Pearl AW, Hsiung MW, et al. Failed medialization laryngoplasty: management by revision surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2001;124(6):615-621. DOI: 10.1067/mhn.2001.116021

15. Cotter CS, Avidano MA, Crary MA, et al. Laryngeal complications after type 1 thyroplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113(6):671-673. DOI: 10.1016/s0194-5998(95)70003-x

16. Hoffman HT, McCulloch TM. Anatomic considerations in the surgical treatment of unilateral laryngeal paralysis. Head Neck 1996;18(2):174-187. DOI: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199603/04)18:2<174::AID-HED10>3.0.CO;2-F

17. McCulloch TM, Hoffman HT. Medialization laryngoplasty with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene. Surgical technique and preliminary results. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1998;107(5 Pt 1):427-432. DOI: 10.1177/000348949810700512

18. Giovanni A, Vallicioni JM, Gras R, et al. Clinical experience with gore-tex for vocal fold medialization. Laryngoscope 1999;109(2 Pt 1):284-288. DOI: 10.1097/00005537-199902000-00020

19. Montgomery WW. XXIX cricoarytenoid arthrodesis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1966;75(2):380-391. DOI: 10.1177/000348946607500207

________________________

© The Author(s). 2021 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and non-commercial reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.